Harley’s Story: Losing His Father and Brother to Suicide

In a collaboration with Wirth Hats, Harley opens up about his father's and brother's suicide, and why talking about mental health matters.

In a collaboration with Wirth Hats, Harley opens up about his father's and brother's suicide, and why talking about mental health matters.

Eleven years apart, on the same date, Harley lost both his brother (in 2008) and his father (in 2019) to suicide.

When Harley speaks about suicide and mental health, it comes from a place of recognizing the importance of having these conversations, and the weight they carry. He doesn’t romanticize pain, and he doesn’t shy away from discomfort. Instead, he speaks with a grounded honesty that reminds us that grief isn’t something to fix, it’s something to tend to, to sit with, and to speak openly about.

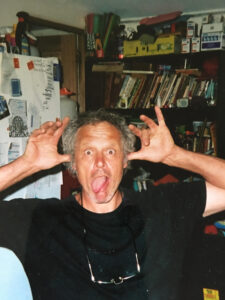

Harley has lived an unconventional life compared to most – growing up in a big, blended family with 4 full siblings and 2 older half brothers, raised on the east coast of Australia. His early childhood was spent on a hippie commune near Coffs Harbour before the family moved to Sydney, and later to a 200-acre property near Nimbin when he was nine. Life there was simple — the kind where you made your own fun but also worked hard to keep the place running. His dad, a set builder who once worked on films like Crocodile Dundee, spent his days working the land and fixing things, while Harley and his siblings explored the bush and helped work around the property.

Harley has been living in Canada for 7 years now, living between Vancouver and Vancouver Island, spending his days surrounded by a close community of friends who share his love for the outdoors, music, and conversations that go beyond the surface.

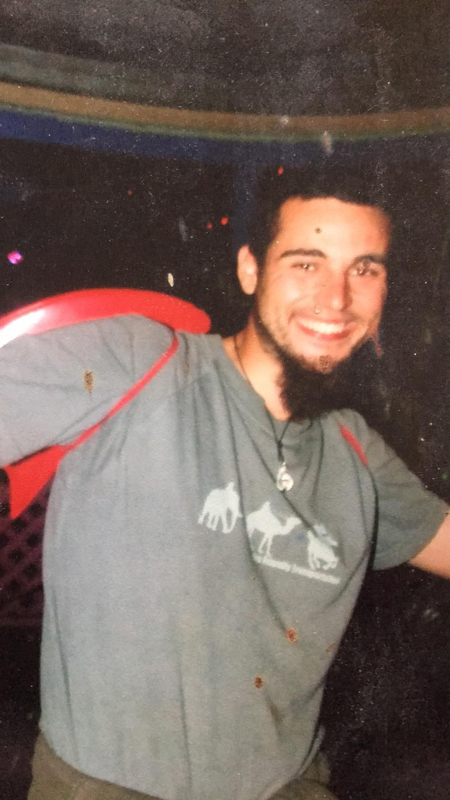

“He was awesome. He’d play with us all the time, and I was his closest brother in age, so I think he favoured me a bit. Back in the day he was taping cassette recordings off Triple J Radio, and would be showing me his favourite songs and artists like Eminem. Which I ended up loving. But yeah, we were pretty close.”

Harley reflects on some of his earlier memories of his older half-brother, Jango, and their relationship. Jango was 5 years older, and although he didn’t always live with Harley and the rest of their siblings while growing up, he still found lots of time and ways to connect with them when he was around.

Harley reflects on some of his earlier memories of his older half-brother, Jango, and their relationship. Jango was 5 years older, and although he didn’t always live with Harley and the rest of their siblings while growing up, he still found lots of time and ways to connect with them when he was around.

Harley was 18 when his older half-brother Jango died by suicide in 2008. It was news that came as a complete shock.

“Back then, no one talked about mental health or suicide. I didn’t even think of it as a possibility. I knew that he was not doing that well and I knew something was going on with him, but yeah, it was a massive surprise.”

After the loss of his brother, Harley navigated grief in a way that’s not uncommon for many – especially as a young adult. Growing up in a society where mental health wasn’t talked about, he turned to coping strategies like partying and drinking, and chose not to share about his brothers passing with many people in his life.

“I went to a therapist once and I just felt so weird about it, so I never went back. And I just bottled it up basically, and tried to ignore it. Back then [talking about mental health] was way more taboo than it is now; so it almost felt like this shame that our family had that I didn’t want people to know about, you know? I didn’t want people to be like, “Oh, why didn’t you help him? Why didn’t you do this or that,” Because I already felt so much guilt about it.”

In 2019, over a decade later, Harley lost his father to suicide on the exact same date that Jango died. In the years after Jango’s death, Harley’s father spiraled into depression and post-traumatic stress.

“I don’t know how we got to the point, but we got to the point where we were talking about mental health, and he confided in me about how he was feeling, about how it all affected him, and that he was feeling suicidal, and he was actually on suicide watch, like, he’d been checked into a mental institute at one point because of the PTSD he suffered from Jango’s death but he hadn’t told anyone else.”

A few years later, Harley had moved to Canada with his girlfriend at the time, thousands of kilometers away but tethered by constant phone calls and emotional weight.

“It was heavy to carry that responsibility of looking after your own father,” he said. “It felt good that I could be there for him and that he had someone to confide in, but I’d leave the phone call just [feeling] so worried about him, and [wondering] what else I can do, and I felt guilty about being [in Canada].”

When his father took his life, the grief hit differently. With 11 years in between the two losses came 11 years of personal growth and societal shifts. Because he’d been through it once before and because he often feared it would happen again, Harley was able to navigate the loss in a healthier, and more open way.

After his father’s death, Harley decided not to hide anymore and posted openly on Instagram about losing both his brother and his dad. Harley wasn’t looking for sympathy, but to break the silence that had once nearly consumed him. “I took that as an opportunity to help other people.”

After his father’s death, Harley decided not to hide anymore and posted openly on Instagram about losing both his brother and his dad. Harley wasn’t looking for sympathy, but to break the silence that had once nearly consumed him. “I took that as an opportunity to help other people.”

The response was immediate. People reached out — some grieving, some suicidal, some just needing to talk. Harley listened. Sometimes he’d stay up late responding to strangers’ messages, offering the kind of empathy he once needed himself.

Harley’s openness began to ripple outward into his friend groups, and he was able to see the shift, especially with his male friends both in Canada, and particularly Australia, where it has a more “suck it up” macho façade culture.

“Our friend group that we have in Aus – even though they are kind of “macho guys” – in that group chat, they’ll tell everyone what’s going on and be pretty vulnerable. I feel like I’ve contributed to that as well, by being open with them, and then other people in the chat will be super open, and other people will see that, and they’re like, oh, it’s not weird to just open up to the boys, you know. I think we’re super lucky to have that kind of culture in our friend group.”

He also got a semicolon tattooed behind his ear, a simple punctuation mark used as a symbol of suicide awareness. It became both a conversation starter and a quiet reminder of why vulnerability matters. “Sometimes it catches me off guard when people ask about it,” he admitted, “but then I remember — that’s why I’ve got the tattoo, to talk about it.”

For Harley, true healing didn’t begin until two years after his father’s death, when he finally started therapy. The sessions became a mirror that reflected not only grief, but the patterns that grief had built.

He realized he’d developed a “fixer” mindset in relationships, drawn to people he could take care of. Through therapy, he was able to trace that back to a core wound: guilt over not being able to “save” his brother.

“It felt different with my brother and my dad in that way that with my dad, I felt like I knew everything. He was so open with me about everything that I felt like I did get the chance to try to do everything that I could [to try and help him]. But with my brother, I felt like I never really got the chance to try, because I didn’t even know that that was a possibility.”

This “lightbulb moment” he found in therapy has since allowed him to work through and resolve some of the guilt he’s been carrying since – a common symptom many survivors of suicide loss experience and struggle with.

Harley also shares how moving countries contributed to being one of the best things he’s done for his mental health – not from a place of “running away from all the problems,” but because of the challenge it was and the resilience it built in his abilities to handle even more challenging situations.

“Do something that scares you. It might sound counterproductive, but once you do it, especially if it’s something you’re anxious about. Once you do it and realize it’s not that bad, then it makes everything else seem so much easier.”

Today, even though separated through physical distance, Harley’s family is closer than ever. Since the loss of his dad, his family does their best to hold regular “check-ins” to talk about mental health. These check-ins – while not easy and often a bit uncomfortable at first – allow the family to stay connected, encourage vulnerability and open communication, and ensure everyone is reminded that they’re not alone through their struggles.

As the oldest of five siblings, Harley feels a sense of responsibility to lead these conversations. “You can see everyone looks kind of uncomfortable. [But] it’s very important that we’re talking about these things.”

He still uses therapy when needed, especially during seasonal dips in mood. He meditates, exercises, gets sunlight, eats well, and leans on friends who know the full story. He also encourages others to do the same, to reach for help long before reaching a breaking point.

Harley acknowledges that it can feel weird, or awkward, or uncomfortable talking about these topics – especially for those who have never experienced a suicide loss, but one of the best ways you can help in reducing the stigma, showing up for your friend, and helping them through their loss is to simply give them the space and permission to speak openly about their experience, and to encourage them to talk about their loved one.

“Advice for people that are friends with people that are going through [this type of loss]: take the lead more; just show up, walk up to their house, be more proactive about it, ask some questions. I am speaking personally again, but we do like to talk about them.”

One of the hardest parts about losing a loved one to suicide is suddenly feeling like you can’t talk about them because you don’t want to make others feel uncomfortable. Even though our society is getting much better at talking about mental health, there’s still often a barrier that keeps people from touching the topic of suicide. But one of the biggest parts of healing is talking about it all and having safe and supportive spaces to do so.

One of the hardest parts about losing a loved one to suicide is suddenly feeling like you can’t talk about them because you don’t want to make others feel uncomfortable. Even though our society is getting much better at talking about mental health, there’s still often a barrier that keeps people from touching the topic of suicide. But one of the biggest parts of healing is talking about it all and having safe and supportive spaces to do so.

Asking simple questions like “What was their name? What did they like to do? What was it like growing up?” can make the world of a difference.

The same goes for anyone struggling with suicidal thoughts: asking for help is never a burden. “Suicide is always a greater one,” Harley said.

Stories like Harley’s remind us that grief doesn’t disappear, it transforms. They remind us that silence helps no one, and that talking about suicide loss, while uncomfortable, can save lives.

At HeadsUpGuys and WIRTH, conversations like this are at the heart of everything. These brands were built on connection, reminding people that being with each other, in our most human moments, matters more than appearances or perfection. Sharing stories like Harley’s helps chip away at stigma, creating space for others to breathe, to heal, and to speak.

Because when one person chooses honesty, it gives others permission to do the same.

And in that shared vulnerability, that moment of being truly with someone else, healing begins.

Sharing a mission to improve mental health awareness, Wirth Hats founder Ben Miller connected us with advocate Hunter, who interviewed her friend Harley for this piece.

Wirth Hats was created to honour Ben’s friend Jakob Wirth, who hoped to one day start his own hat company. To date, Wirth Hats has sponsored thousands of hours of therapy for those who need it most.

Hunter is a writer, photographer, and aspiring filmmaker passionate about telling stories that connect and inspire – exploring themes based in mental health, environmentalism, and mindful travel.

As a suicide-loss survivor after losing her mom in 2019, Hunter turned to creativity to not only heal for herself, but to show others the beauty to be found in life – working with organizations and businesses like WIRTH, Sea Shepherd Australia, Zorali, Sea to Summit, and VIMFF.

More of her work can be found at goldenhourcommunity.com.

Our thanks to Harley for opening up about his experience, and to Hunter for putting this interview together.

Too many men suffer in silence. Become a peer supporter for the men in your life.

In this four-part course (15–20 min each), you’ll learn what effective peer support looks like, how to show up for others, and how to stay grounded while doing so.